Beth was seven months pregnant when we found out we couldn’t get the cash to finish the house. There was no kitchen. There wasn’t even a room where the kitchen should have been, just bare stud walls and exposed, diagonal-plank subfloor that gave us a great view of the basement below. A pleasant November draft came singing its way up from the darkness every time we walked by. We were reduced to cooking out of a hand-me-down toaster oven and an electric skillet I’d had since college.

When the kind old nurse at the birthing class asked if we’d all finished preparing our nurseries, a sort of yelping, desperate laugh sprang out of my throat before I could stop it. Everyone was busy sticking Winnie The Pooh stickers over cribs. I’d just finished ripping out the only bathroom in the house, leaving us both to shit in a camp toilet set up in what would eventually become our daughter’s room.

My grandfather passed the year before we were married. Of the long line of bastards the man stared down in his life, esophageal cancer was the one that got the better of him. Somehow, I hadn’t told him I was engaged to that bright and fierce and beautiful girl he’d met once or twice. I’d mean to call, then get distracted. Put it off for tomorrow or the next day. He was sick, sure, but he had been for years as diabetes and the cells in his own body conspired against him. It didn’t seem important. There was time to pick up the phone and dial the number. Time to hear his voice lift when I said, “Hey, Pappaw.”

Time to hear him clear his throat and brighten. Time to hear, “Whadda ya say, boy?” in the distance.

Except there wasn’t. My oldest uncle found him on the floor of that kitchen. He spent his last days in the hospital downtown, the one with the good view of the Tennessee River and the valley it carved. Then he was gone. Buried in the clay of Union County, the place that killed his daddy. The place that damn near killed him as a boy with disease and poverty and malnutrition. The place that gave him somewhere to rest at the end of it all, soft and green and gorgeous these days. Appalachia on its best behavior.

Beth and I bought his house from the estate. It wasn’t something we planned. Hell, it wasn’t something we could afford, really. But I couldn’t stand the thought of a stranger in that place. We moved from Virginia with no jobs or clear course ahead. We leapt with the hope that Knoxville would catch us. And it did.

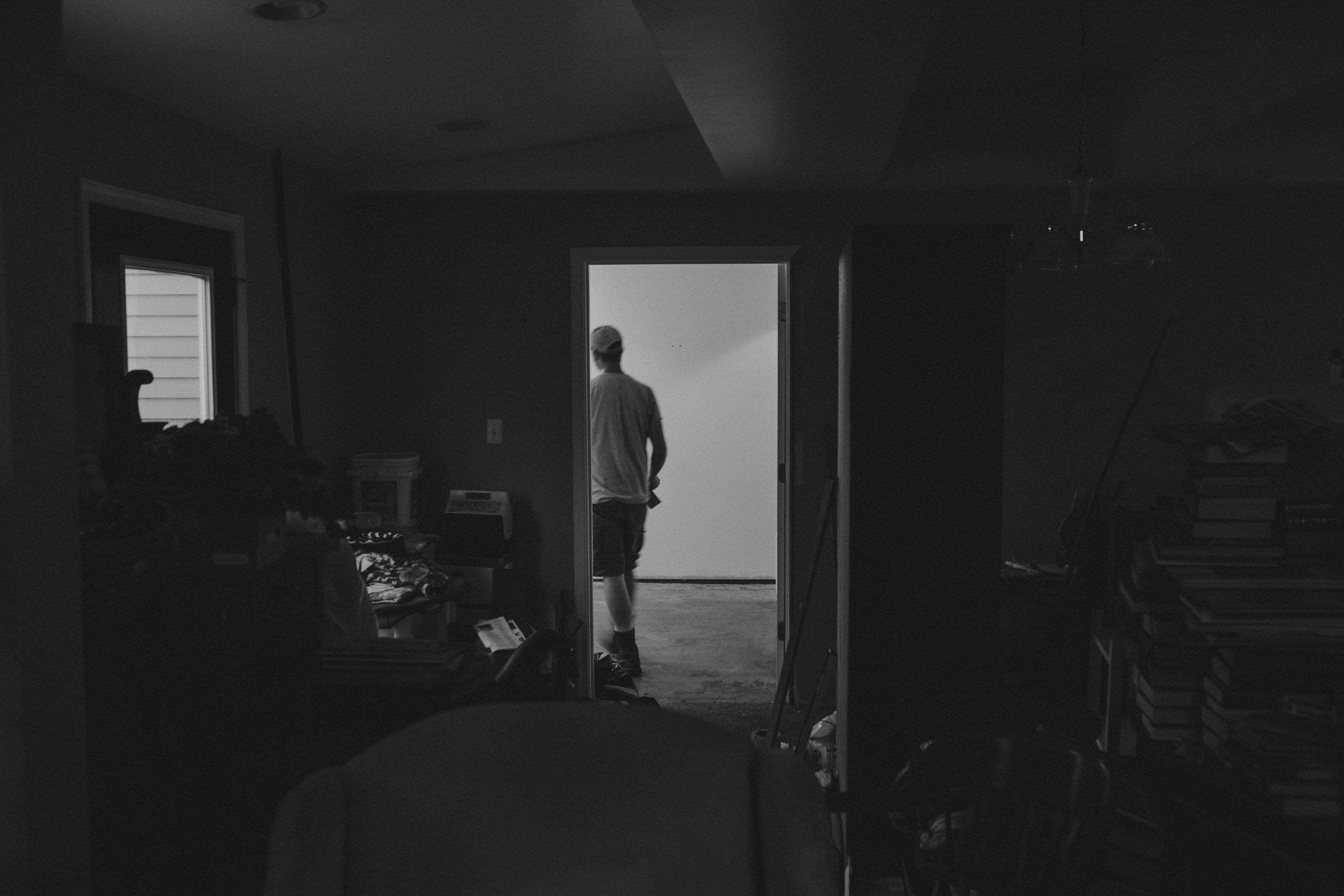

I worked to renovate the house, to brighten the thing some. Pulled down dark paneling and ripped up thick brown carpet to reveal gorgeous hardwood below. Painted walls, hung trim, discarded the hollow-core doors that reminded me of the mobile home nightmare of my early days. Replaced them with solid pine. Did it all slowly. All out of pocket.

When Beth told me she was pregnant, the vast majority of the house was undone. The main hall, the dining room, the kitchen, the living room, the bathroom. I threw myself at it. Became a wild and thrashing zealot, sleeping little or not at all. Enlisted the help of a small army of friends and family to get me through it. We were wild hammer swingers.

I knew I’d need a loan for the kitchen and the bathroom. There just wasn’t any way to do the work right without the financial help. I put it off as long as I could—did as much of the work as possible before going to the bank, hat in hand. Except, there was a problem: No one would loan us the cash without a new appraisal, and the house wouldn’t appraise for shit with no kitchen and no bathroom. I was stuck.

Furious, too. At my stupidity. At the bank. At time. At putting us in this idiot position by dismantling my grandfather’s house. I started looking for solutions. What could we sell? What could we do without?

It was Beth’s parents who pulled us out of that fire. Loaned us the money when they didn’t have it to lend. I have always been dwarfed by her family’s generosity. By their kindness towards me and others. Her father, a Virginia Baptist preacher who used to spend every Halloween dressed as the Devil, had every right to tell me to go drown in a river when I came to ask for his daughter’s hand in marriage. I had broken her heart twice by then, and I made no pains to hide my atheism or my jagged edges from him or his wife. He simply asked that I keep an open mind about his family’s faith, and warned me that if I ever laid a harsh hand on his daughter, I’d have a new understanding of the phrase, “biblical wrath.”

We finished the bathroom, and had most of the kitchen buttoned up by the time we brought our daughter home one bright and cold February day. And while there were many hands that went into making that happen, Beth’s parents were the ones who made it possible.

And it was more than paint and trim. More than tile and tub. It was the ability to bring my daughter into a home we were proud of. To let her spend her first fragile days in the house that had sheltered three generations of Bowman family. My grandfather’s house. Our house.

It’s why we’re back in Virginia now, to help them lift a burden they couldn’t otherwise lift themselves, the way they helped us when we needed it more than I would have said.